A Practical Guide to UIFSA

By Joseph W. Booth*

*Joseph W. Booth (joe@boothfamilylaw.com) was the ABA Family Law Section Liaison to the ULC during the drafting of the 2001 and 2008 versions of the UIFSA. He practices family law in Kansas and has served as an adjunct professor for Washburn University School of Law. Booth is a past chair of the Family Law Section’s Child Support Committee and the current vice chair of the Section’s Publications Development Board. In addition to his law degree, Booth holds a master of divinity degree. He is a fellow of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers and the International Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers.

The Uniform Interstate Family Support Act (UIFSA) is the only truly uniform act in family law. Because it is a federally mandated state statute and has recently been revised, all states have the same Act.

The legislators of each state were granted scant leeway to modify the uniform Act. As the Uniform Law Commission’s Legislative Fact Sheet says, the “2014 federal legislation requires all states to enact the 2008 UIFSA Amendments as a condition of continuing to receive federal funds for state child support programs. Failure to enact these amendments during the 2015 legislative session may result in a state’s loss of important federal funding.”

There is no shortage of resources explaining the provisions of the UIFSA. Three of the most outstanding and comprehensive ones are: Symposium on International Enforcement of Child Support, 43 Fam. L. Q. 1 (2014); John J. Sampson & Barry J. Brooks, Integrating UIFSA (2008) with the Hague Convention of 23 November 2007 on the International Recovery of Child Support and Other Forms of Family Maintenance, 49 Fam. Law. Q. 179 (2015); and Kurtis A. Kemper, Annotation, Construction and Application of Uniform Interstate Family Support Act, 90 A.L.R. 5th 1 (2001). Despite these excellent resources, however, the UIFSA remains a source of confusion and consternation for bench and bar alike. What follows is intended to be a useful overview of the Act that hopefully reduces that confusion and consternation.

The Most Recent Version: 2008

The most recent iteration of UIFSA, which contains nine articles composed of various parts and sections, was drafted in 2008. This 2008 version incorporates the 2007 Hague Convention on the International Recovery of Child Support and Maintenance. The federal legislative enactment lagged behind until 2014, when the 2014 Preventing Sex Trafficking and Strengthening Families Act was signed into law. All U.S. states and territories have adopted the 2008 version. Until the passage of this current version of UIFSA, there were three prior versions: 1992, 1996, and 2001. One had to look carefully to see which version any particular state or territory had enacted. Now there is but one version uniformly adopted.

One of the most important aims of the UIFSA is to eliminate multiple support orders for the same beneficiary. Uniform laws are crucial to this endeavor because uniformity can lessen the risk that, after parentage and support obligations are established, courts in different states will duplicate or issue alternative support orders or conduct parallel enforcement proceedings.

Watch Your Language

UIFSA is one of those acts that creates its own lexicon of precisely defined terms, so any practitioner seeking to understand the Act must first carefully review section 102, “Definitions.” For example, a “support order” is defined as

a judgment, decree, order, decision, or directive, whether temporary, final, or subject to modification, issued in a state or foreign country for the benefit of a child, a spouse, or a former spouse, which provides for monetary support, health care, arrearages, retroactive support, or reimbursement for financial assistance provided to an individual obligee in place of child support. The term may include related costs and fees, interest, income withholding, automatic adjustment, reasonable attorney’s fees, and other relief.

Unif. Interstate Fam. Support Act § 102(28). (Note that citations in this article are to the 2008 UIFSA version published by the Uniform Laws Commission; individual state numbering systems may differ slightly.)

How UIFSA Uses Jurisdictional Restraints

UIFSA occupies a unique position in law. UIFSA is state law but the content is mandated by federal legislation, which results in a virtually unprecedented use of individual state law to execute a federal treaty. UIFSA manages an integrated interstate and international support system primarily by empowering each state to exercise its jurisdiction as broadly as is constitutionally permissible to establish support. Conversely, however, it limits each state’s jurisdiction to modify support.

Further, each state’s jurisdictional reach is given full faith and credit. For example, sections 201–202 are the long-arm provisions of UIFSA, standing separate from each state’s general statutory provisions. These bestow jurisdiction on “any other basis consistent with the constitutions of this State and the United States for the exercise of personal jurisdiction.” See Unif. Interstate Fam. Support Act § 201(a)(8), a codification of Burnham v. Superior Court, 495 U.S. 604 (1990). However, the very next provision of the Act then sharply limits the state’s own jurisdiction by stating:

The bases of personal jurisdiction set forth in subsection (a) or in any other law of this state may not be used to acquire personal jurisdiction for a tribunal of this state to modify a child-support order of another state unless the requirements of Section 611 or 615 are met, or, in the case of a foreign support order, unless the requirements of Section 615 are met.

Unif. Interstate Fam. Support Act § 201(b).

UIFSA proceeds without regard to whether jurisdiction is being exercised for other purposes. For example, child custody jurisdiction is almost universally controlled by the Uniform Child Custody Jurisdiction and Enforcement Act (UCCJEA), which follows the child’s location with only some regard to the location of the parents once all have vacated the last state in which a child custody order was issued. These different acts often place child custody and child support jurisdiction in different states.

In order to understand why many of the jurisdictional constraints work as they do, one has to understand the influence of constitutional restraints. The definitive case is Kulko v. Superior Court, 436 U.S. 84 (1978), which mandates personal jurisdiction over the obligor for issuance of support orders. Because of the ongoing nature of child support, there is a likelihood that these orders will need to change as material changes occur for the obligee, obligor, and the beneficiary. To manage these ongoing needs, once jurisdiction is exercised by a state, it continues while the obligor, the individual who is an obligee, or the child are still residents of the state. This authority is referred to as continuing exclusive jurisdiction (CEJ). So sections 205 and 202 dictate that, even when the obligor has left the state, the issuing state continues to be the jurisdiction for modification of the order.

Establish or Modify

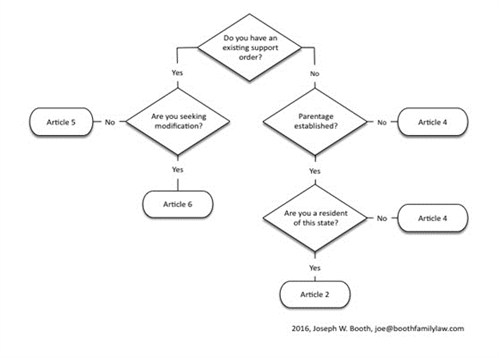

A major source of confusion over UIFSA deals with this fact: the Act’s jurisdictional rules almost completely contradict one another depending on whether establishing or modifying a support order is at issue. Figure 1 illustrates which article in UIFSA is applicable.

Establish or Modify? Figure 1

Establishing a Support Order

When establishing a new order for support, the first step is to ascertain whether parentage has been established. If it has not been, UIFSA applies to the process of establishing parentage under that state’s rules or otherwise establishing parentage (by obtaining, for example, an acknowledgement of parentage) and beginning support. UIFSA leaves the process of establishing parentage to other laws, and nonparentage is not a defense to the enforcement of an order. UIFSA calls upon the courts of the various states to work together to assert one another’s jurisdiction whenever appropriate. So a court in one state may not have jurisdiction over the establishment of support or parentage but can initiate proceedings in a sister state that should then respond by pursuing the action. Once the proper tribunal is established, article 2 provides the rules of procedure for establishing a child support order and managing the ongoing jurisdiction.

If it comes to pass that more than one state tribunal has initiated proceedings at the same time, UIFSA section 204 gives preference to the state in which proceedings were filed first. But care is taken to prevent multiple orders.

The preference for the first state is rebutted when the following conditions are met: when a later-filed petition in another state has perfected service before service is perfected in the first state; when the contesting party in the later state has challenged jurisdiction in the state where the petition was first filed; and, if appropriate, when the later state is the home state of the child. To accomplish this, the Act provides that a tribunal is barred from exercising jurisdiction if an action for support has been filed with another state or foreign tribunal before the first tribunal’s answer date has passed; if the contesting party files a timely objection in the second state; and if the second jurisdiction is the home state of the child. UIFSA section 204 is one of the few UIFSA provisions to contain a stated preference for litigation in the child’s home state.

Enforcing a Child Support Order in Other States

UIFSA’s article 5 deals with the most common form of enforcement—the income withholding order. The way UIFSA extends one state’s jurisdiction into another state is elegant in its simplicity. No registration or court filing in the nonissuing state is required. Unif. Interstate Fam. Support Act § 501. Then UIFSA sets out requirements for the employers within every state to recognize and obey the income withholding order from outside the state. Unif. Interstate Fam. Support Act § 502. The remainder of article 5 offers guidance on how to respond to multiple orders pertaining to the same employee, provides immunity for proper compliance, penalizes for noncompliance, and creates a procedure to contest the order by registering the income withholding order in the employer’s own state and filing a contest. The Act also empowers the local enforcement entities of each state to enforce other states’ orders without the necessity of registration.

A support order may be registered in any other state for enforcement or modification. Article 6 provides the substance and procedure for registration. The process of registration is set out in section 602 and is intended to be straightforward and include due process safeguards. This registration process begins with a letter; two copies of the order or orders to be registered, one to be certified; a sworn statement indicating what, if any, arrearages exist; and finally, what information is known about the obligor, including address, social security number, employer information, and a description and location of nonexempt property. (There are special procedures when there are multiple orders for the same obligor but different beneficiaries.) The registered order is filed and notice is served on the nonregistering party. Once registered, the foreign order is then enforced in the same manner as any order issued by that state.

If jurisdiction exists, the registration may include a motion for other relief such as, for example, modification of support. Or, once registered, any party may file a motion to be heard if jurisdiction exists.

Once registered, the law of the issuing state still governs the nature, extent, amount, and duration of payments ordered; computation methods of payments; interest accrual; etc. For enforcement purposes, the longer of the two states’ statutes of limitation applies. Unif. Interstate Fam. Support Act § 604.

Once registered, the opposing party is given notice. The nonregistering party then has twenty days to respond. Failure to respond creates a default, the order remains registered, and all alleged arrearages become a judgment. Unif. Interstate Fam. Support Act § 605. The nonregistering party may then request a hearing to challenge the validity of the order, bring forward other applicable orders, or challenge the allegation of arrearages. Section 607 sets out the defenses, which include the allegations that the order sought to be registered is: void for want of personal jurisdiction over the obligee; obtained by fraud; vacated, suspended, or modified; under appeal; subject to any defense available under the issuing state’s law; fully or partially paid; time barred; or not the controlling order. If any of these defenses are found applicable, the registered order’s effect is limited accordingly. But if none apply, the order is confirmed.

In the day-to-day practice of law, local counsel generally files a petition for registration and serves the nonregistering party with the packet of pleadings and orders to be registered. There is no filing fee for registering an order under UIFSA. It is recommended that the court be provided an order confirming the registered support order if the nonregistering party was served and failed to proffer a defense.

Modifying an Existing Order

Modification rules and procedures are in articles 2 and 6 of the Act. Earlier we touched on CEJ (continuing exclusive jurisdiction), and CEJ is a unique feature of UIFSA. Just be aware that the UCCJEA purposefully left to UIFSA the unique moniker of CEJ; when the UCCJEA speaks of continuing exclusive jurisdiction, it does not use the acronym CEJ.

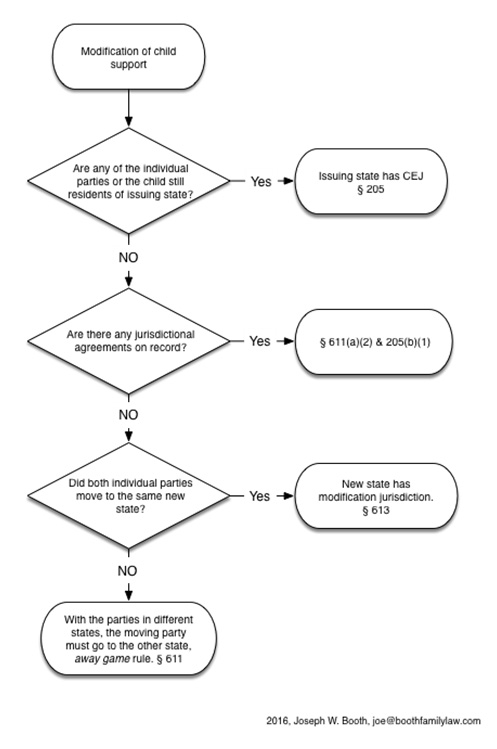

As we know, there are child support orders and spousal support orders. UIFSA section 211 states that spousal support orders are subject to the jurisdiction of the issuing court. Spousal support orders are modifiable only by the original issuing state. For child support, the jurisdiction to modify may change; as mentioned above, the issuing court has CEJ until the obligor, the beneficiary, or the obligee (as a person, because other entities could be obligees) are all residing in another state. A new jurisdiction must be found when all obligees, beneficiaries, and obligors no longer reside in the state. See Figure 2.

Where to Modify Figure 2

Determining the Controlling Order when More than One Order Exists

If only one support order deals with the same obligor and the same child, that order is deemed the controlling order. But multiple orders for the same obligor and the same child result in more than one state appearing to have CEJ, UIFSA does not require any action in those issuing tribunals. UIFSA sets out a simple method to determine the controlling order. First, the order arising from the current home state of the child controls; second, if none of the orders arise from the child’s current home state, then the most recent order controls. Unif. Interstate Fam. Support Act § 207.

Consents Made on the Record

In a rare exception to the premise that subject matter jurisdiction cannot be established by consent, UIFSA sections 205(b)(1) and 611(a)(2) allow for consents made on the record in the issuing state to confer jurisdiction away from a court that would still have CEJ. Deference is given to another state's tribunal if that state has jurisdiction over at least one of the individual parties or it is the state where the child resides.

Residency or Domicile?

There is divergence in court decisions, but UIFSA tracks the residence, not domicile, of each obligee, obligor, and child. The following cases reflect the inconsistencies in interpretation. State ex rel. SRS v. Ketzel, 275 P.3d 923 (Kan. Ct. App. 2012) states that residence, and not domicile, was what the drafters of UIFSA intended, while In re Marriage of Amezquita & Archuleta, 124 Cal. Rptr. 2d 887 (Ct. App. 2002) and Kean v. Marshall, 669 S.E.2d 463 (Ga. 2008) hold that UIFSA’s residency requirements really should be analyzed as domicile. UIFSA uses the term “residence” and that is exactly what was meant. The statesmanship, the academic acumen, and the experienced linguistic specificity of the Commission should not be cast aside as mere sloppy syntax; “residence” means just that. However, look to local law to determine how to define “residence.”

The Away-Game Rule

With the obvious exception of the situation in which all the individual parties and the subject child relocate to the same new state, UIFSA section 611 gets around the jurisdictional constraints discussed above by requiring the party moving to modify the support to play an "away game" and come to the jurisdiction where the nonmoving party resides. This results in the nonmoving party's state having jurisdiction over the moving party because he or she voluntarily submitted to the jurisdiction, and the nonmoving party is subject to jurisdiction by virtue of his or her residence.

Duration of Support

Section 611 states that the new state will use its own child support guidelines and its own procedural law, but the duration of support remains as it was in the original order. So an order that originated from a state that terminates the child support obligation when the child reaches eighteen years of age (or completes high school) will still terminate the support when the child reaches eighteen even if subsequent orders are issued from a state that would normally terminate the support obligation at twenty-one years of age or older. And the inverse is true as well. A state that normally terminates child support at eighteen years of age but that assumes jurisdiction over an order from a state providing for child support into majority will keep the child support order in effect until it would have terminated under the original order.

International Application

A discussion on the international aspects of the new Act and the associated treaty enacting the Hague Convention on the International Recovery of Child Support and Other Forms of Family Maintenance is beyond the scope of this discussion. But article 7 of the UIFSA is the enacting legislation that triggers application of state law. As discussed, this effect on state law is the result of a federal mandate requiring all states to pass UIFSA 2008, which modified earlier versions of the Act to require that foreign orders under the Convention be enforced in a manner very similar to that required for other states’ orders.

The most difficult hurdle for U.S. participation in the Convention, which is also a continuing problem, arose from what is often called creditor- or child-based jurisdiction. Kulko requires personal jurisdiction over the obligor in order to assure due process. In creditor- or child-based jurisdiction, those foreign entities issue orders creating obligations over obligors without regard to the contacts or jurisdictional association with the foreign entity. Any enforcement of creditor- or child-based orders that would not otherwise have jurisdiction over the obligor is not constitutionally permissible. So UIFSA directs a court to first consider whether there was a basis for the issuing entity’s jurisdiction over the obligor even if it did not rely on that basis for that order. If a basis can be found, then the order is enforceable. If the order is not enforceable, the obligor is likely subject to the jurisdiction of that U.S. court, and UIFSA directs it to simply establish a new support order relying on the jurisdiction that is constitutionally permissible in light of the presence of the obligor.

In Sum: Creation of a One-Order System

The UIFSA is a uniform state law that creates a one-order system for establishing parentage and support by maximizing the jurisdictional reach of any state operating in this context. Once an order is established, UIFSA then minimizes the jurisdictional ability of the court to modify the order. Such orders are then enforceable without court action primarily through the income withholding order system, which operates throughout the country via local law to mandate employers’ compliance with out-of-state orders, thereby assuring that employers who follow the orders are immune from prosecution. By controlling a state’s jurisdiction in this way, each support order is easily enforced.

* * *